Sketching with code

Issue 286: Treating code like a pencil, not a blueprint

A common concern with coding through Gen AI is that the outputs are so high fidelity that they narrow the solution space. But you can run into the same problem with Figma. Long before generative AI, I was sketching in code—and the distinction matters. My love for a spatial canvas to explore infinite ideas applies just as much to programmatic drawing.

Sketching with code is a different mode, but it feels natural to me. I can often draw faster on a keyboard than with a stylus. Over the years, I developed a physical sketching system—symbols, color coding, hierarchy through line weight—as a shorthand to accelerate ideation. Sketching with code is the programmatic extension of that same system. The shorthand I built for pen and paper trained my instinct for what to feed the machine.

My approach to sketching with code

Before I share how I sketch with code in the age of LLMs, it’s worth establishing what matters to me regardless of whether I’m writing code by hand or directing AI to generate it.

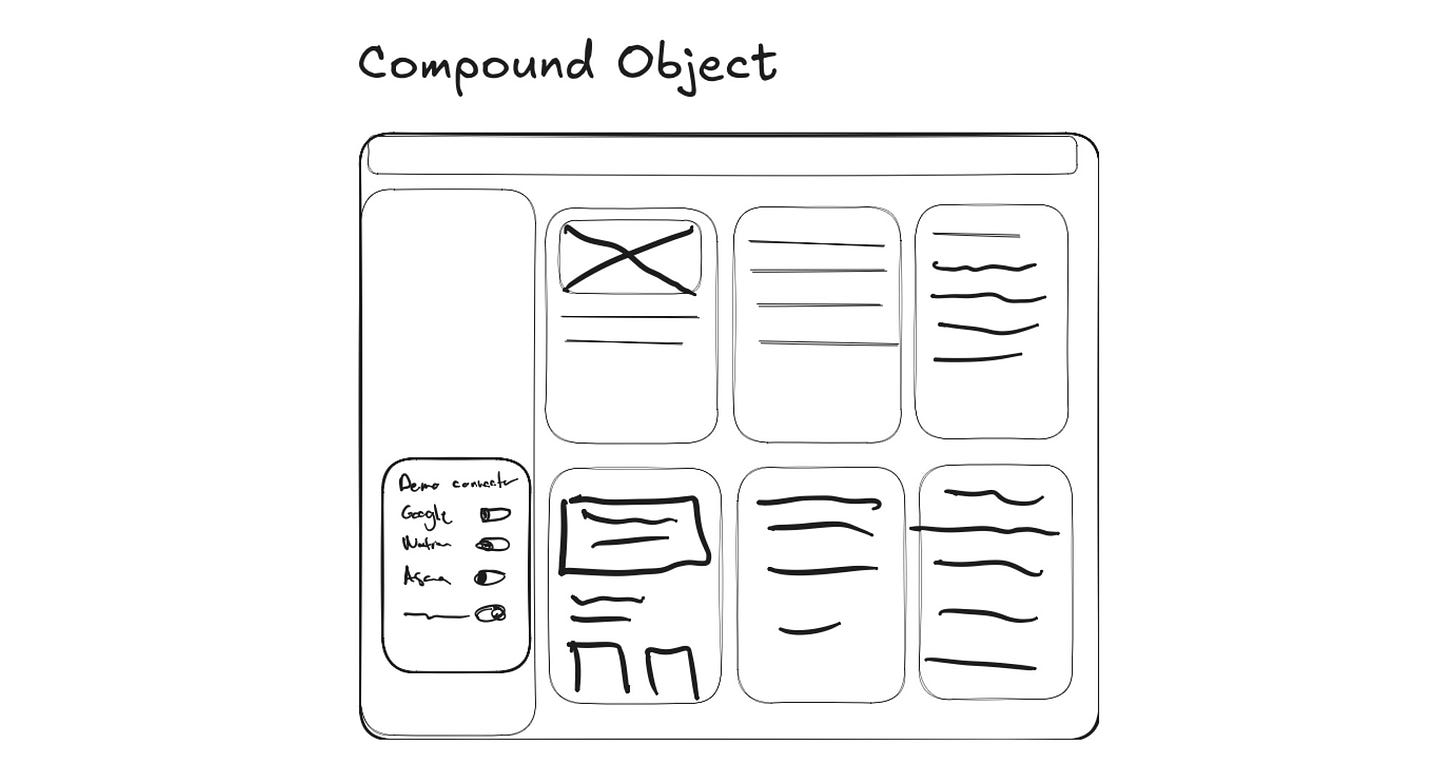

I start without a design system. This is deliberate. Production-grade components carry assumptions—spacing, hierarchy, interaction patterns—that narrow the solution space before you’ve had a chance to explore it. If I’m proposing a feature, the design system is the right starting point. But in exploration mode, the system comes later. Sketches are for divergence; design systems are instruments of convergence.

Second, I sketch for technical fidelity. Early in my career I relied on Axure RP, but eventually switched to coding in HTML, CSS, and JavaScript. The power of code as a sketching medium is that fidelity is a dial, not a binary. A code sketch can be a single HTML file with hardcoded data—just enough to show a flow and get a reaction—or it can connect to a real API and handle edge cases. Most people assume that opening a code editor means working in high fidelity. It doesn’t. A <div> with a background color and placeholder text is just as low-fi as a sticky note—it just happens to run in a browser.

Upload drawings to LLMs

Ben Grace, Product Designer at Atlassian, recently shared with our team a walkthrough of how he uses Excalidraw as the context for his projects in Replit. I remember the words of a mentor describing computer vision simply:

Computers can read what we see.

That blew my mind. We often forget how long computers have been reading visual input. In 1989, Yann LeCun trained a neural network to read handwritten zip codes off envelopes at Bell Labs. By the late ‘90s, his system was processing over 10% of all checks written in the U.S. In 2017, Tony Beltramelli’s pix2code took a GUI screenshot and generated working code for iOS, Android, and web. Then in 2023, tldraw shipped “Make it Real” — draw a rough UI sketch on a canvas, click a button, and GPT-4V returns a functional HTML prototype. The gap between what humans draw and what computers can execute has been closing for 35 years. In the last two, it effectively collapsed.

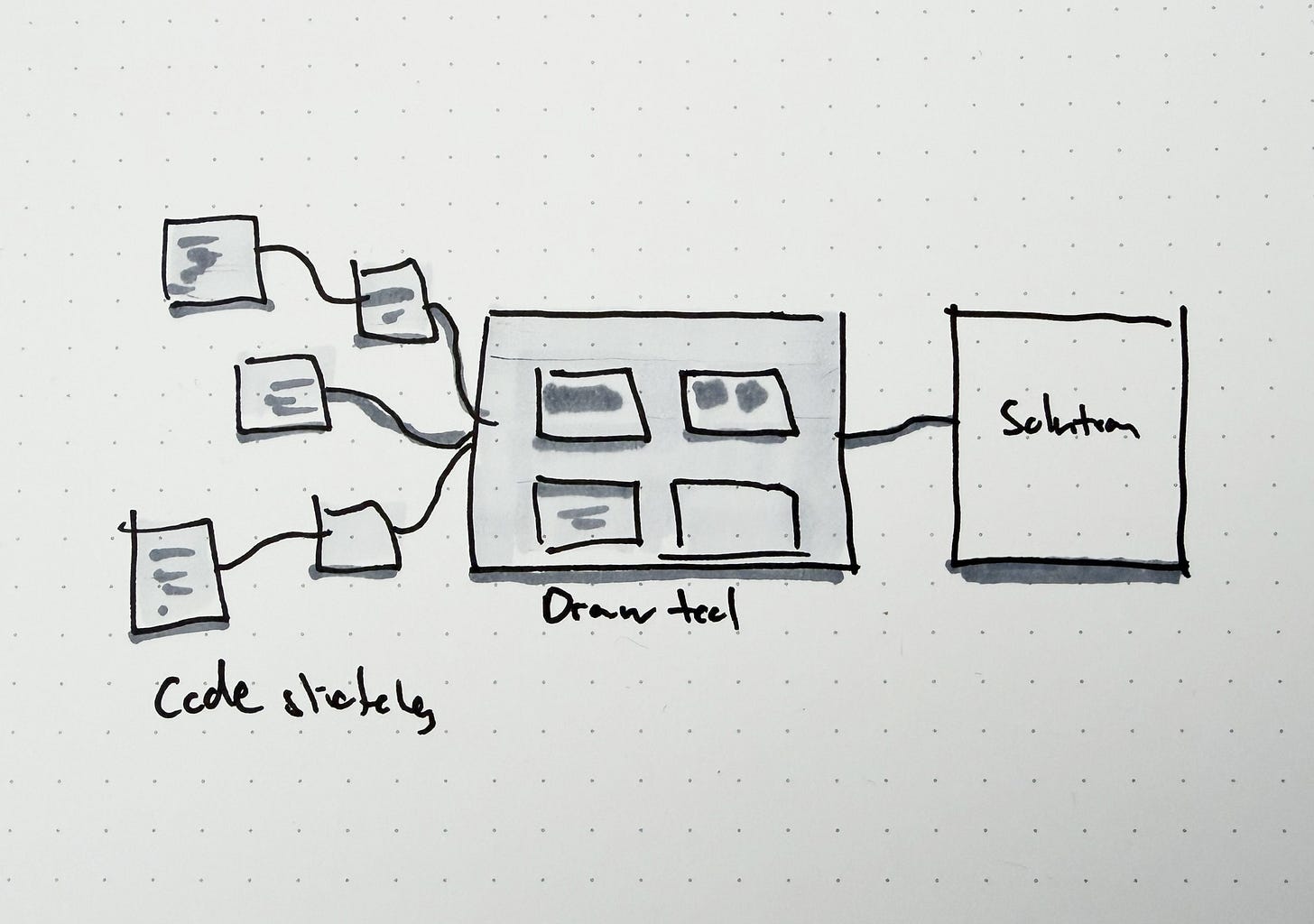

Most of my sketching with code today starts on paper. I upload wireframes, screenshot annotations, and hand-drawn sketches to have the LLM explore code variations.

My favorite prompt is “Build 10 variations of this” to rapidly explore.

Shaping up technical fidelity

Early in my career, designers used Parse as a back end to prototype iOS apps. You’d define a data model, wire up a few API calls, and suddenly your prototype remembered state, handled multiple users, and behaved like a real product. That experience taught me something lasting: data and models are structure, and structure is a powerful sketching technique.

When I sketch with code today, technical fidelity is the dimension I dial up first. Visual fidelity—colors, spacing, type—layers on easily later. The questions that matter early are structural: What’s the data model? Where does state live? What happens when this list is empty, or has 10,000 items?

Design system interlock

Once I have a few solutions worth pursuing, I bring in the design system. This is where sketching ends and shaping begins—where a rough concept starts to inherit the constraints and conventions of the product it might become.

Previously, this transition was high effort. You’d rebuild your prototype from scratch using production components, re-mapping every layout decision to the system’s grid, tokens, and interaction patterns. It felt like translation work—tedious and lossy. The sketch had energy; the systemized version often didn’t.

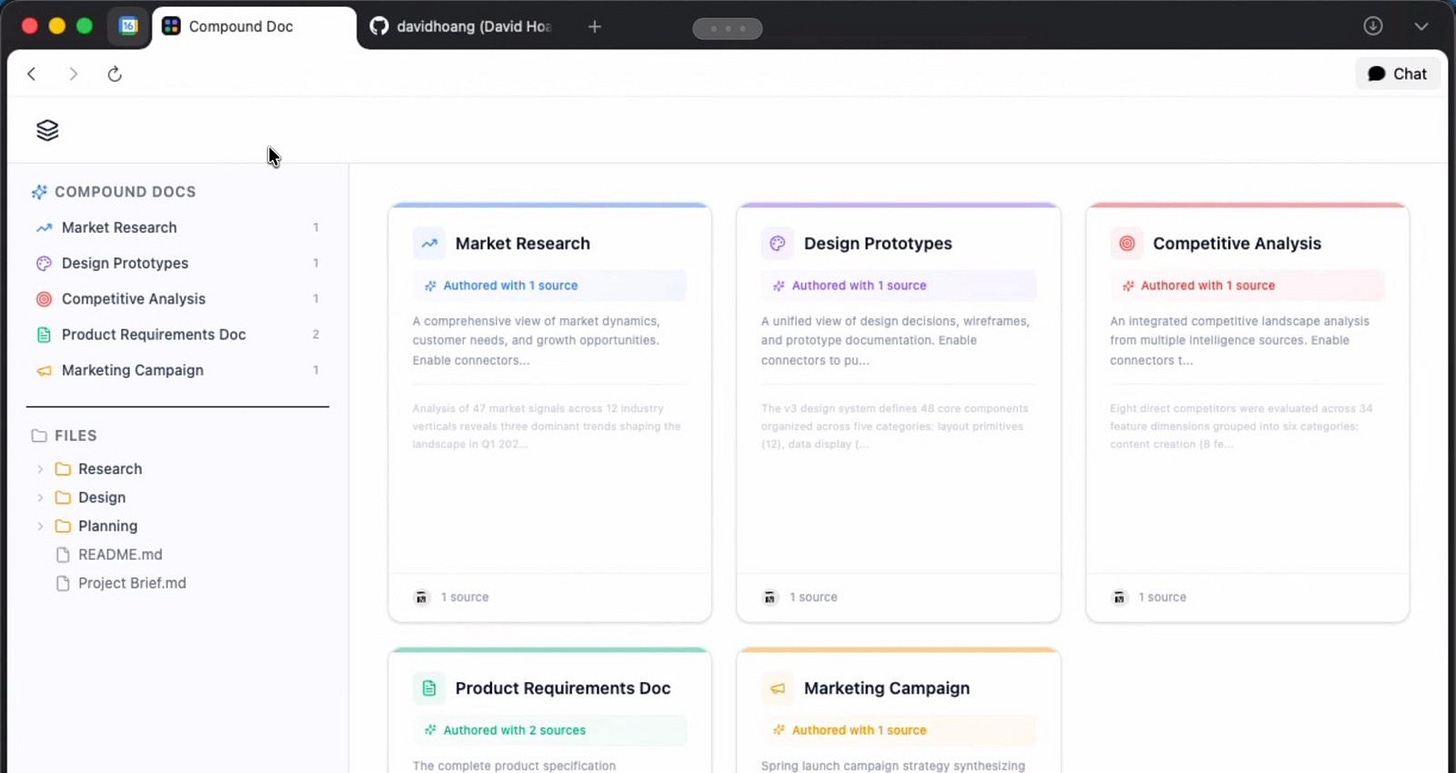

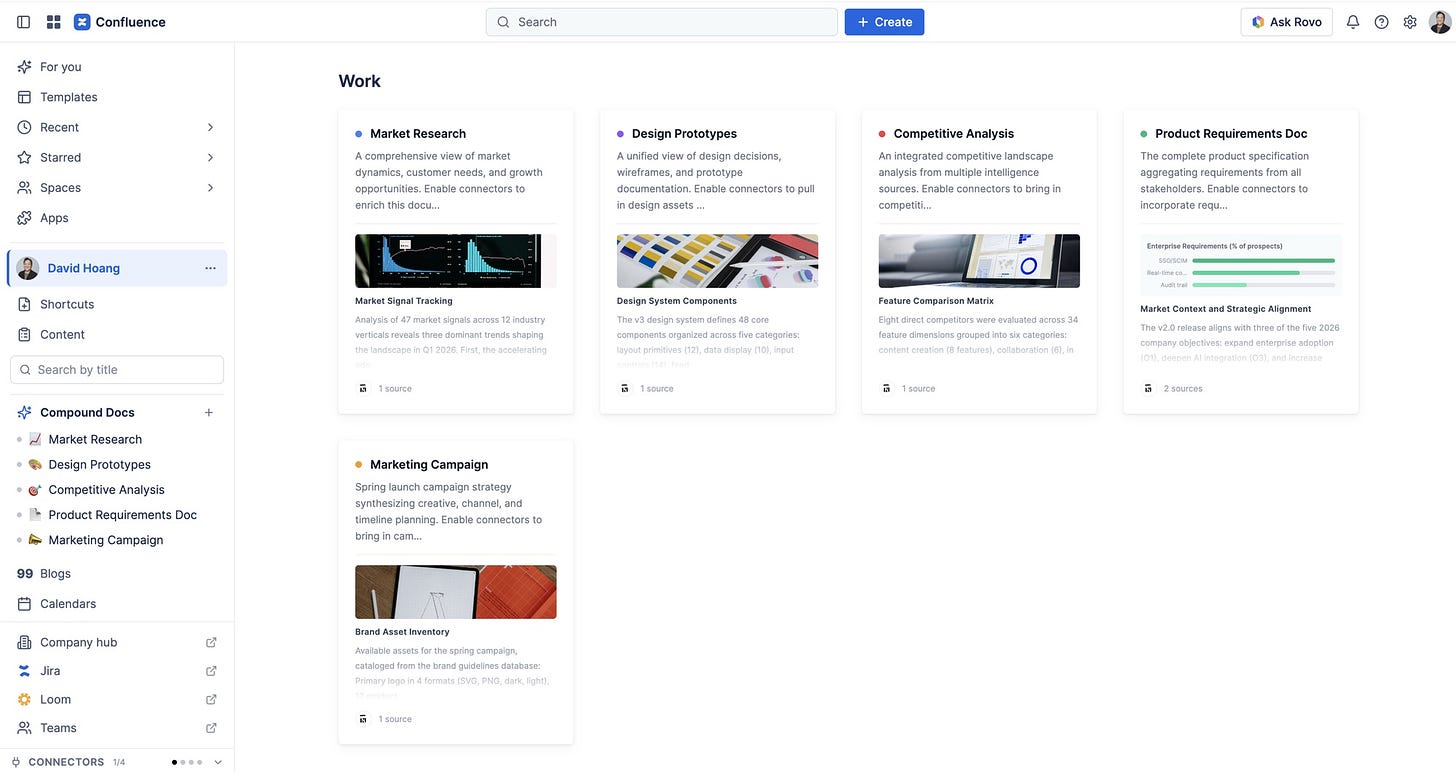

Now that gap is collapsing. At work, I can point an LLM at Atlassian’s Atlaskit component library or connect to our MCP server, and it will re-skin a rough code sketch with real design system components in minutes. The structure I built during the sketching phase—data model, state management, flow logic—carries forward. What changes is the surface: a plain <select> becomes an Atlaskit dropdown, a hardcoded list becomes a dynamic table with sorting and pagination baked in.

This is the interlock I care about. The design system isn’t a starting point—it’s a finishing move. You sketch unconstrained to explore the problem space, then snap your best ideas onto the system’s rails to see if they hold up. The LLM makes that snap nearly instant, so I can run the full loop—sketch, evaluate, systemize—multiple times in a single session. Ideas that break under the system’s constraints get caught early. Ideas that survive get stronger.

Because I started without the design system, there are style overrides—the UI won’t be pixel-perfect. But after screenshot revisions with the LLM and micro-prompting, I can get it to a realized state.

Contributing to new values and patterns

For design systems to remain relevant, they need contributions. Too often, the system calcifies—it caps innovation instead of enabling it. Sketching with code surfaces those gaps naturally. You find the places where the system falls short, and in doing so, you find opportunities to contribute back. To innovate on a system, you have to break it apart and put it back together.

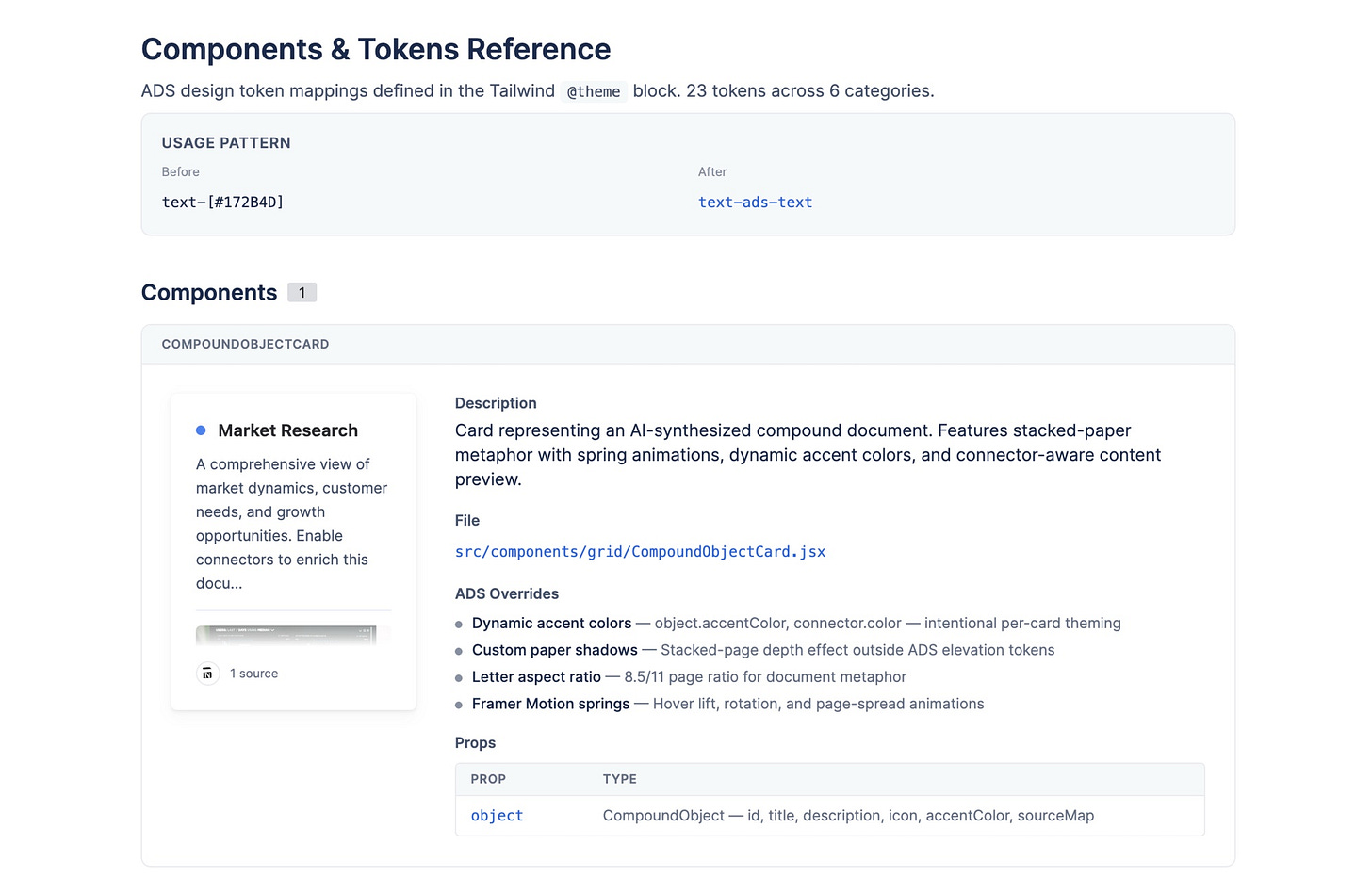

This mode of working also lets you build your own tools along the way. I’m an admittedly lazy documentor, so instead of manually tracking proposed changes to our design system, I built a component tracker that documents them for me.

In addition to exploration tools, code sketches are communication tools. A running prototype changes the conversation in a room faster than any slide deck. People stop arguing about what something might feel like and start reacting to what it does feel like. A scrappy code sketch deployed to a URL has more persuasive power than a polished presentation. It builds conviction because it’s real—it runs, it responds, it has edges you can poke at. If you want to move a decision forward, demo before the memo.

Recap

If you start with the design system, you’ve already narrowed what’s possible. Resist the urge to reach for production components when you’re still exploring. Feed the LLM with images of your sketches and annotations—hand-drawn wireframes, screenshots, whatever captures the idea—and let it generate variations in code. Once you’ve found directions worth pursuing, bring the design system back in and interlock it with your findings. Weirdly, making apps is itself a form of sketching to get to the final app you want to build.

Hyperlinks + notes

pix2code: Generating Code from a Graphical User Interface Screenshot — Tony Beltramelli (2017)

Make Real, the story so far — tldraw’s sketch-to-code demo