The plan is the program

Issue 276: Knowledge engineering and plans as an atomic unit

“The plan is the program,” is something Tyler Angert said when working on Amjad Masad’s TED Talk. At the time, it captured how modern tools collapse intent and execution. Looking at it now, the phrase feels less like a metaphor and more like a literal description of how work is getting done.

This is not just an observation about LLMs. It’s about how humans and machines are starting to share the same planning surface.

Transformers brought prompt engineering. As systems grew more capable, we learned that prompts alone were insufficient, and context engineering emerged to scaffold intent. What’s happening now feels like the next step: plans themselves are becoming the unit of knowledge. That shift introduces a new layer of practice—what I’ll call knowledge engineering.

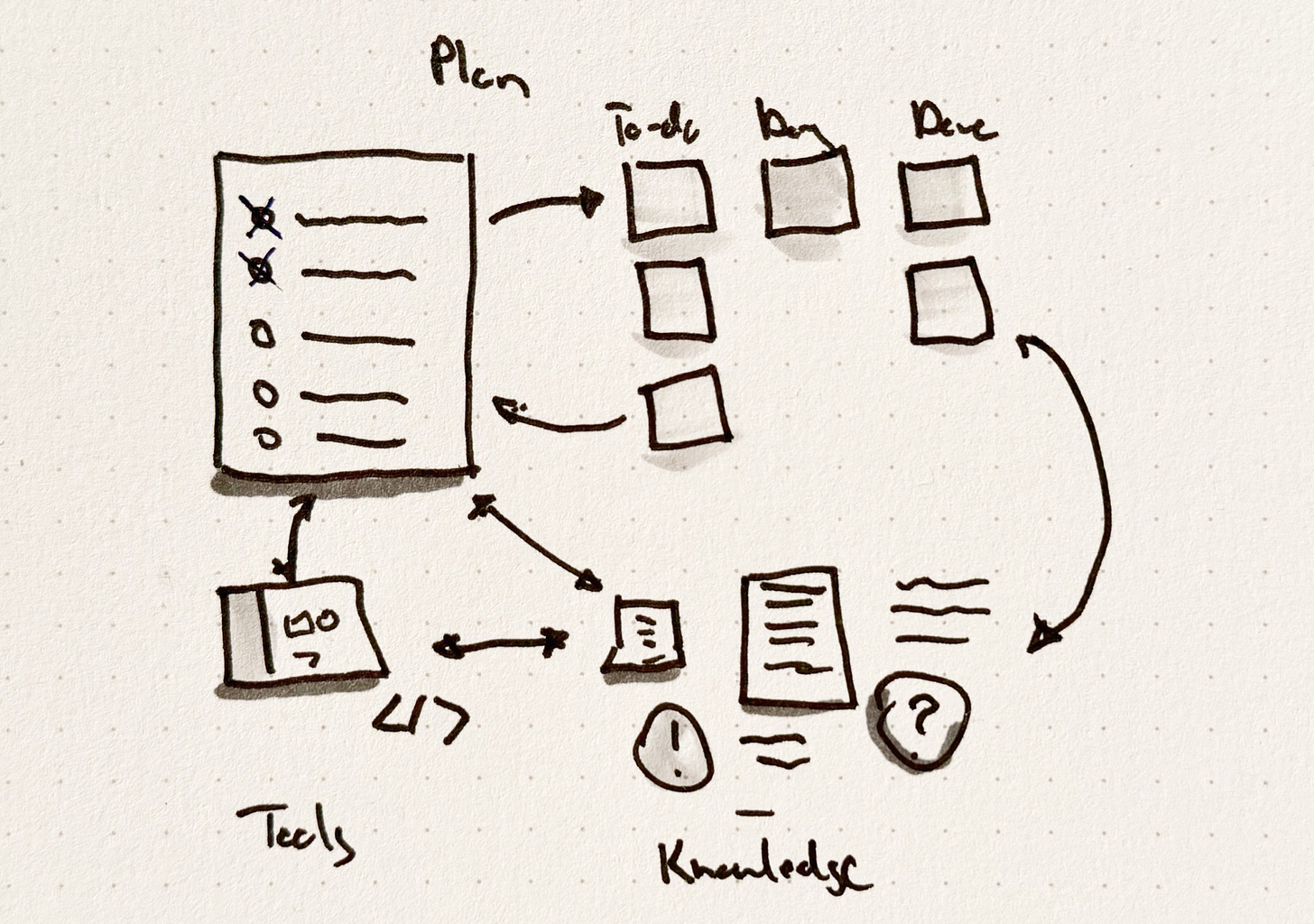

The atomic nature of plans

Planning used to be something we did before work began. A document. A ticket. A spec. Something upstream of execution.

That separation no longer holds.

Plans are becoming atomic units of work in the same way frames are atomic units in a Figma file. A plan can stand alone or be nested inside another plan. It can be provisional or durable. It can be reviewed, revised, forked, or discarded. And increasingly, it can be executed.

We’re seeing this pattern across AI-powered tools. A plan is proposed. A human reviews it. Adjustments are made. Execution begins. The plan becomes the interface between intention and action.

This changes who the plan is for. Historically, plans coordinated people. Now they coordinate systems. Humans are no longer just authors of plans—they’re editors and judges of them.

For individuals, planning has always been intimate. A grocery list on paper. A Kanban board for a wedding. A markdown checklist buried in a repo. These worked because the planner and executor were the same person.

Once you introduce multiple people (or machines), planning becomes more fragile. Tasks multiply. Dependencies emerge. Subtasks reference other subtasks. What began as a cognitive aid can quickly become a liability.

Speed and execution reduce planning cycles

Execution speed changes what a plan needs to be.

When execution is slow, plans must be defensive. They anticipate edge cases, handoffs, and misunderstandings. Much of traditional project management exists to compensate for latency. When execution is fast, it reduces dependencies, allowing planning to be thinner.

AI collapses the distance between thinking and doing. You no longer need a fully articulated plan to start. You need a reviewable one. Plans exist long enough to be inspected, corrected, and acted upon.

Planning starts to look less like a phase and more like a loop. Propose. Execute. Observe. Refine. The plan survives only as long as it remains useful.

Personal and team workflows

Team planning doesn’t work without agreement. Planning systems fail less often because of tooling limitations and more often because of misaligned expectations. People plan differently—lists, diagrams, prose. These differences are usually invisible until they collide.

Teams need shared primitives even if individual execution styles vary. Uniformity matters less than legibility. Everyone should be able to understand the plan, even if they wouldn’t have authored it that way themselves.

AI tools surface this tension because they force plans to be explicit. The system needs something concrete to operate on. Ambiguity has to be resolved—or at least acknowledged—before execution begins.

In that sense, AI doesn’t just accelerate planning. It exposes its weak spots.

Plans as context

One reason product managers picked up vibe coding so quickly is that much of their job already involved setting context. They did it for engineers, designers, and stakeholders. Now they do it for models.

Prompt engineering taught us how to ask. Context engineering taught us what to include. Knowledge engineering is about structuring intent over time so it remains usable.

This becomes especially clear when you look at knowledge bases.

Wikis were manageable when content was scarce, and authorship was centralized. That model breaks when information becomes abundant. We’ve seen this before. Photo storage had the same arc previously. Physical albums gave way to digital folders, which gave way to cloud libraries containing thousands of images. The result wasn’t better memory—it was amnesia at scale.

Once recording became automatic, knowledge bases started to fill up fast. Meetings are captured by default. Transcripts and summaries accumulate. Very little of it gets revisited. The problem isn’t whether something exists. It’s whether it’s meaningful in the moment you need it—and whether you trust it enough to act on it. Plans help because they force knowledge to earn its place. Information only matters if it supports a decision or an action.

Real-time breakdown of work

Planning and execution now happen on the same surface.

Work is decomposed dynamically, not fully upfront. The system proposes the next steps. Humans decide whether they make sense. Constraints surface during execution, not speculation. Being wrong early becomes cheap.

This shifts decision-making. You don’t decide everything before you build. You decide enough to begin, then stay engaged as the system fills in the gaps.

A plan accumulates history as work happens.

This is why traditional trackers start to feel misaligned. Tools like Jira were built for prediction—pointing, estimating, and sequencing work before execution begins. As execution speeds increase, those rituals matter less. What matters more is traceability: what ran, what changed, what was reviewed, and what shipped.

Subagents

At the AI Engineer Code Summit, Replit President and Head of AI Michele Catasta described subagents not as a feature, but as a control structure.

In his framing, a core agent loop reasons about the problem, decides what work can happen in parallel, and dispatches tasks to subagents with scoped responsibilities. One might refactor code. Another might write tests. A third might update documentation. These subagents don’t coordinate directly with each other. They report back.

What matters is the merge.

Catasta emphasized that decomposition must be “merge-aware” from the start. Parallel work is planned with reintegration in mind. This avoids the illusion of progress—what he referred to elsewhere as “painted doors”—where an agent looks productive without delivering durable outcomes.

This mirrors how effective human teams already operate. Work branches. Specialists operate in parallel. Someone integrates the pieces. Subagents make that structure explicit in software.

For humans, the role shifts again. You’re no longer enumerating steps. You’re shaping the loop—defining constraints, judging results, and deciding what gets merged.

The plan is no longer a description of work. It is the execution model.

Control surfaces for plans

Prompt engineering was about language. Context engineering was about inputs. Knowledge engineering is about making intent legible at scale.

Plans become durable knowledge objects. They encode intent, constraints, and decision history. They persist long enough to be reused, adapted, or audited. The value shifts from raw information to executable understanding.

This is not better documentation; it is making intent legible to both humans and machines. The most interesting planning software today doesn’t ask, “What do you need to do?” It asks, “What is already happening?”

Execution trails matter more than task lists. Review and approval replace assignment. Systems optimize for traceability, reversibility, and refinement. Code generation has advanced at a pace few expected. Other phases—review, observability, quality—are still catching up.

What’s already clear is that planning is no longer upstream of work. It’s the surface we operate on—where intent is shaped, execution is steered, and outcomes are judged.

The plan is the program.

Hyperlinks + notes

Shopify Winter ‘26 Editions → Congrats to the Shopify team on shipping both incredible product experiences and a site to commemerate the milestone

State of AI Coding: Context, Trust, and Subagents | Turing Post

Cool, yes, this is where we move to. The plan = the product. The intent is written, and the program is executable. We iterate faster with more trace and feedbacks.

Hey, great read as always. This idea of plans being atomic units of work is so spot on. What do you see as the biggest challenge for humans coordinating these systems?