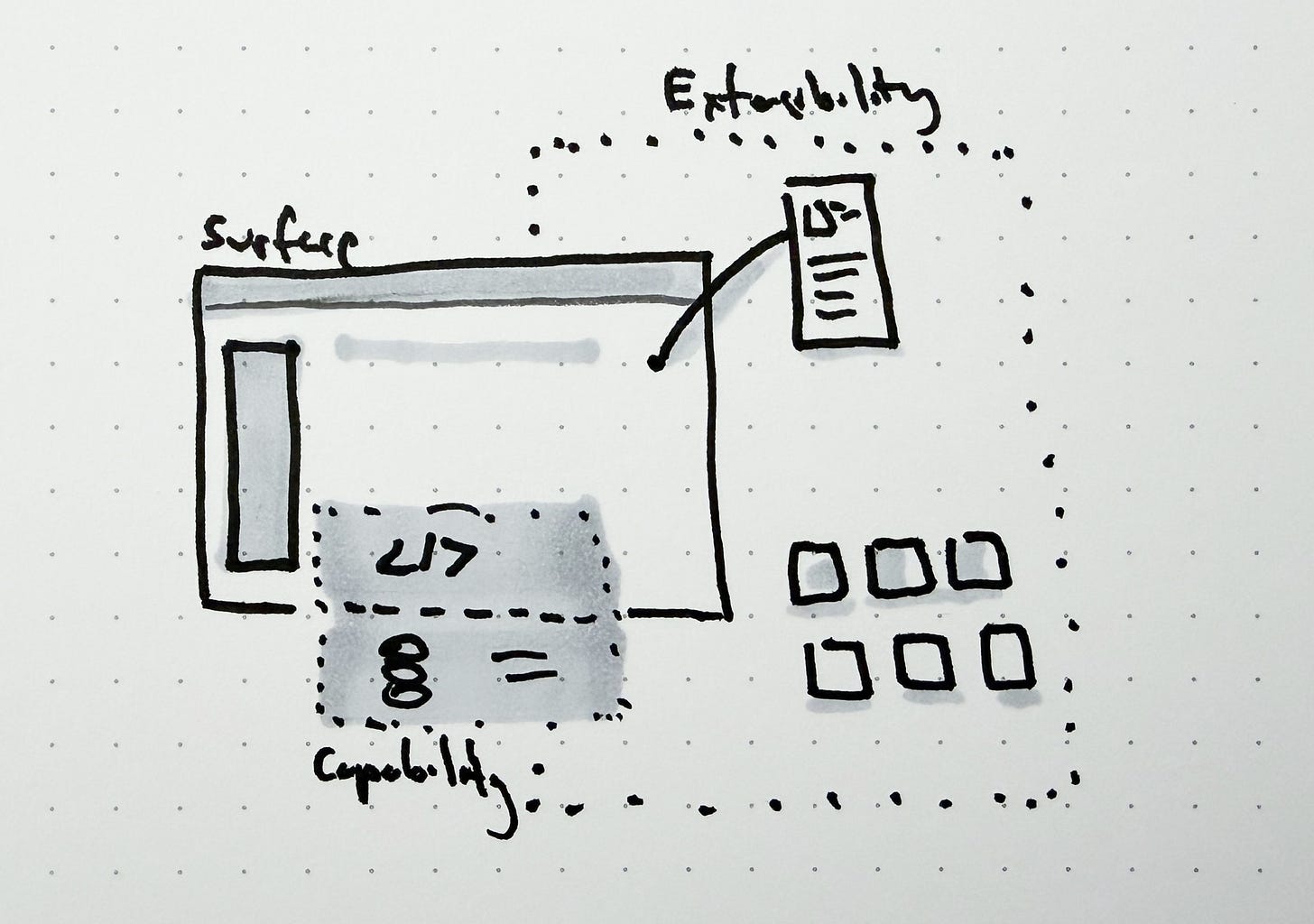

Surfaces, capabilities, and extensions

Issue 284: Future casting opinionated platforms

Throughout my career, I’ve had the pleasure of working across many different focuses: consumer, growth, design systems, marketplaces, platform, and so much more. Each focus area has its own approaches and incentives. Over time, I amalgamated them into three pillars to distill it to the simplest form: surfaces, capabilities, and extensions. Each layer has a different job, and each demands a different posture from the team building it.

Every owner of a platform eventually faces the same question: how opinionated should we be? Too rigid and you alienate the people who outgrow your defaults. Too flexible, and you ship a blank canvas that nobody knows how to use.

An unopinionated platform serves well for maintaining consistency with the past, but it does not future-proof it. My approach to platform design is simple: find key pillars to signal where the platform is going. The best platforms make them for you, then give you the tools to override when you know better. Let’s look at the three pillars in more detail.

Surfaces

Surfaces are the app views and screens that humans interact with and that agents use. The common touch points are typically buttons, layout, workflows, and defaults that people see upon app launch. This is where the strongest opinion should manifest.

Surfaces are the app views and screens that humans interact with—the UI. They’re the buttons, the layouts, the workflows, the defaults that greet you when you open the product for the first time. This is where opinion should be strongest.

A well-designed surface conveys a point of view on how work should be done. Notion has an opinion about what a blank page should look like. Figma has an opinion about where your tools live. These aren’t arbitrary choices. They’re decisions that reduce the cognitive load on every user who doesn’t want to think about configuration before getting to work.

The risk is when surfaces become ceilings. When your surfaces are too rigid, you can only deliver experiences for the global maxima of your current audience.

Capabilities

The APIs, data models, and building blocks that power your surfaces are the capabilities; the native platform primitives you offer. As the engine underneath, this is the “what you can do” layer, and it should always be broader than what any single surface exposes.

The long-term value of a platform usually lives here, not in the UI. Stripe’s API is far richer than its dashboard. Shopify’s admin is one surface over a massive capability layer. The surface gets you in the door, but the capabilities are what keep you from outgrowing the platform.

The mistake teams make is conflating these two layers. Just because the UI doesn’t show something doesn’t mean the platform can’t do it. And just because you built a capability doesn’t mean it needs a button. InVision is the cautionary tale—they had a strong surface, simple prototyping from Sketch to a clickable prototype, but never deepened the capability layer underneath. When Figma shifted the paradigm, there was no engine to adapt. The capability can only be as powerful as users being aware of it on the surface.

Extensibility

Extensibility is the ecosystem layer—the bits you can add on. Plugins, integrations, marketplace apps, and third-party tools that plug into your platform’s capabilities. This is where you admit you can’t anticipate every use case and invite others to fill in the gaps.

In ecosystem design, interoperability requires exposure. You’re maintaining open tunnels between your system and others, and that means giving up some control. But the alternative is building walls that users will route around anyway. Urban planners have a term for this: desire paths, the trails people wear into the grass when the sidewalk doesn’t go where they need. You can fight desire paths, or you can pave them.

Good extensibility feels like the platform was designed for your specific use case, even when it wasn’t. VS Code’s extension model, Slack’s app ecosystem, WordPress’s plugin architecture—these aren’t bolted-on afterthoughts. They’re first-class layers that treat third-party developers as co-creators of the experience.

Opinionated platforms in practice

The framework is the easy part. The hard part is the work. Here’s how I think about the approach.

Use the ecosystem to prototype the future

Your ecosystem is a signal. Before you build a capability natively, look at what people are building on top of your platform with extensions, integrations, and workarounds. The ecosystem is prototyping for you—every popular plugin is a feature request, and every Zapier workflow is a diagram of what your surfaces are missing.

This is how you figure out what to naturalize. When an ecosystem solution gets enough traction that it feels like it should just be part of the product, that’s your cue. You’re not guessing what to build—you’re watching what people already need and pulling it into the platform. The ecosystem does the discovery. You do the integration.

Know where to incur debt to deliver value

You don’t have the luxury of a full rewrite. Nobody does. Building an opinionated platform means making strategic bets about where to invest deeply and where to accept imperfection in the service of shipping value.

This is a debt decision. You might ship a surface that’s more opinionated than your capabilities currently support, knowing you’ll need to backfill the engine later. Or you might open up extensibility before your API is fully baked, because the ecosystem feedback will teach you more than another quarter of internal design. The point is to be intentional about the tradeoff. Know what you’re borrowing against and have a plan to pay it back. The worst platform debt is the kind you didn’t know you were taking on.

Signal the future through new surfaces and components

When you’re ready to move the platform forward, don’t rewrite everything—introduce a new surface that embodies the direction you’re headed. One app, one view, one component that carries the new intention.

Apple did this with Music. When Apple Music launched, it wasn’t just a streaming service bolted onto iTunes. It was the app that signaled where the entire platform and ecosystem were going. The design language, the interaction patterns, the content-forward approach—Music was the proof of concept for a new era of Apple’s software. It was opinionated in a way that iTunes had stopped being. And it told developers and users alike: this is what’s next.

You can do the same thing at any scale. Ship one surface that demonstrates the new world. Let it coexist with the old. Let people experience the opinion before you ask them to commit to it. The new surface becomes the lighthouse—it shows the direction without forcing the migration.

Hyperlinks + notes

Ghostty is my Terminal emulator of choice now. Try it and consider supporting them

Why your departments are converging, and the implications of collapsing the stack...

System x Human x Machine | A great newsletter by my colleague Lewis Healy