Natural light week

Issue 277: Embracing the seasonality of the winter break

The New World —directed by Terrence Malick and shot by Emmanuel Lubezki is often described as a film shot with natural light (mostly true, but not in a purist sense). Day scenes were filmed using real sunlight, often during early morning and late afternoon. Interiors relied on windows and reflected daylight instead of studio rigs. Night scenes used firelight, candles, and torches, with just enough augmentation to remain readable. Artificial light wasn’t eliminated; only used when absolutely necessary. When it appeared, it was indirect and meant to disappear.

What Malick and Lubezki were after wasn’t realism for its own sake. It was a different relationship to constraint. Time of day mattered. Weather mattered. Shadows were allowed to exist. Faces weren’t lit for the camera; they were embedded in the environment.

That decision shaped everything downstream: when scenes could be shot, how long they lasted, where the camera could move, when the day ended. Natural light wasn’t an aesthetic preference. It was an operating rule.

I think about that every winter when I take a break. I feel the same resistance show up. Not to work itself—I still want to think, plan, and make sense of what I’m building—but to the way I’m asked to work. Shorter days lower my tolerance for constant visibility. Backlit screens feel harsher. Video calls are heavier. Even when the workload is reasonable, the posture starts to feel wrong.

It took me a few years to stop fighting that signal.

Now, winter is when I deliberately adjust my work routine. I step away from LED screens and video calls and move onto quieter surfaces. Paper and pen come first. An e-ink tablet without a front light handles what needs to stay digital. I work within daylight hours and stop when the light fades—not because I’m finished, but because continuing past that point costs more than it gives.

The seasonality of winter encourages me to consolidate and reduce where there is abundance. I review old ideas and breathe life into them. I outline and plan well so I can spring into execution upon return. I reconnect threads that moved too fast during the year to settle properly. Without constant screen stimulation, I stay with problems longer before trying to resolve them.

This wasn’t a planned ritual. It emerged from pattern recognition. Every winter I ignored the seasonal shift, I entered spring mentally duller than I needed to be. Every winter I respected it, I came back clearer—more decisive, more grounded in what actually mattered.

Natural light week

Having a natural light week isn’t actually about my belief on powerful screens or analog. It serves more as a cleanse of what’s most important. Like natural light in Malick’s films, the constraint changes what’s possible downstream by forcing different decisions upstream.

Winter has its own grammar. This is how I work inside it.

I don’t have a natural light week to recover from burnout. I use it to recover before burnout can happen. The work I’m doing is engaging, and I love the people I work with. I take the week not to seek something new, but to capture what is already going well.

In the most engaging work, you lose a source of energy, or emit too much. In this case, it’s constant simulation. The light meeting weeks still are in front of my Studio Display looking at designs, code, and docs. Most of my day was still still spending most of my day under artificial light, moving between windows, calls, and threads. There was no obvious overload—just no trough. No moment where the system actually returned to baseline.

That’s the condition this practice responds to.

Light, screens, and baseline stress

Most screens are emissive. They don’t just display information; they project light directly into the visual system, weighted toward the blue end of the spectrum. There’s plenty of research showing how this suppresses melatonin and disrupts circadian rhythms—especially later in the day—but the more interesting effect is cumulative.

When your eyes never experience real contrast—bright daylight followed by genuine dimness—the body loses a clear signal for when to be alert and when to wind down. Sleep quality erodes quietly. Recovery becomes partial.

Natural light works differently. Daylight exposure, especially earlier in the day, anchors circadian rhythms and improves sleep depth later on. It calibrates the body. Working within natural or ambient light isn’t about avoiding technology. It’s about letting the body read the environment correctly again.

Remote workers require more screen recovery from

Remote work didn’t start in 2020. I’ve been lucky to work remote for more than 20 years. However, the pandemic moved the entire workday over to video screens instead of finding the optimal way to work remotely.

In an office, video calls were punctuated events. You walked to a room. Your posture changed. Your eyes shifted from near to far. Even exhausting meetings ended with physical transitions—a hallway, a window, another presence.

In remote work, those edges vanish—a Zoom call is rarely just a call. It’s one screen layered on top of documents, chat threads, notifications, and tabs that remain visible—even when muted. The brain never fully exits one context before entering the next. There’s no decompression between interactions, only continuous task switching under constant visual stimulation.

On a video call, you’re compensating for latency, interpreting compressed nonverbal cues, tracking turn-taking, and often monitoring your own image. Seeing yourself keeps part of your attention in performance mode. Even when the conversation is straightforward, the cognitive tax is higher than in-person or audio-only communication.

Over the course of a remote workday, that cost compounds. Attention isn’t gone because the work is difficult. It’s gone because the system never stood down.

Removing video calls for a period doesn’t eliminate collaboration. It changes its texture. Conversations move to documents, writing, or audio-only check-ins. Responses slow slightly, but depth increases. Without the pressure of continuous on-camera presence, attention becomes available again.

What returns isn’t productivity in the narrow sense. It’s cognitive bandwidth.

Working at a lower frequency

Working on paper allows me to change the pace. I write fewer words. I crossed things out more often. I hesitated before starting a sentence because I knew revising it would take effort. That hesitation turned out to be useful. It forced me to decide what was worth writing down before I wrote it.

On a screen, capture is cheap. You can write quickly, reorganize endlessly, and defer structure until later. On paper, structure has to appear earlier. You don’t get infinite retries. You commit, even when the thought is incomplete. That changes how long ideas are allowed to stay unresolved.

I noticed I stayed with problems longer. Instead of producing multiple variations, I worked through a single line of thinking until it either clarified or collapsed. Fewer branches, more depth.

Typed text always feels provisional to me. It’s easy to delete, easy to overwrite, easy to abandon. Handwritten notes feel different. Even rough ones feel like they occupy space. They’re harder to ignore, which makes me more willing to return to them.

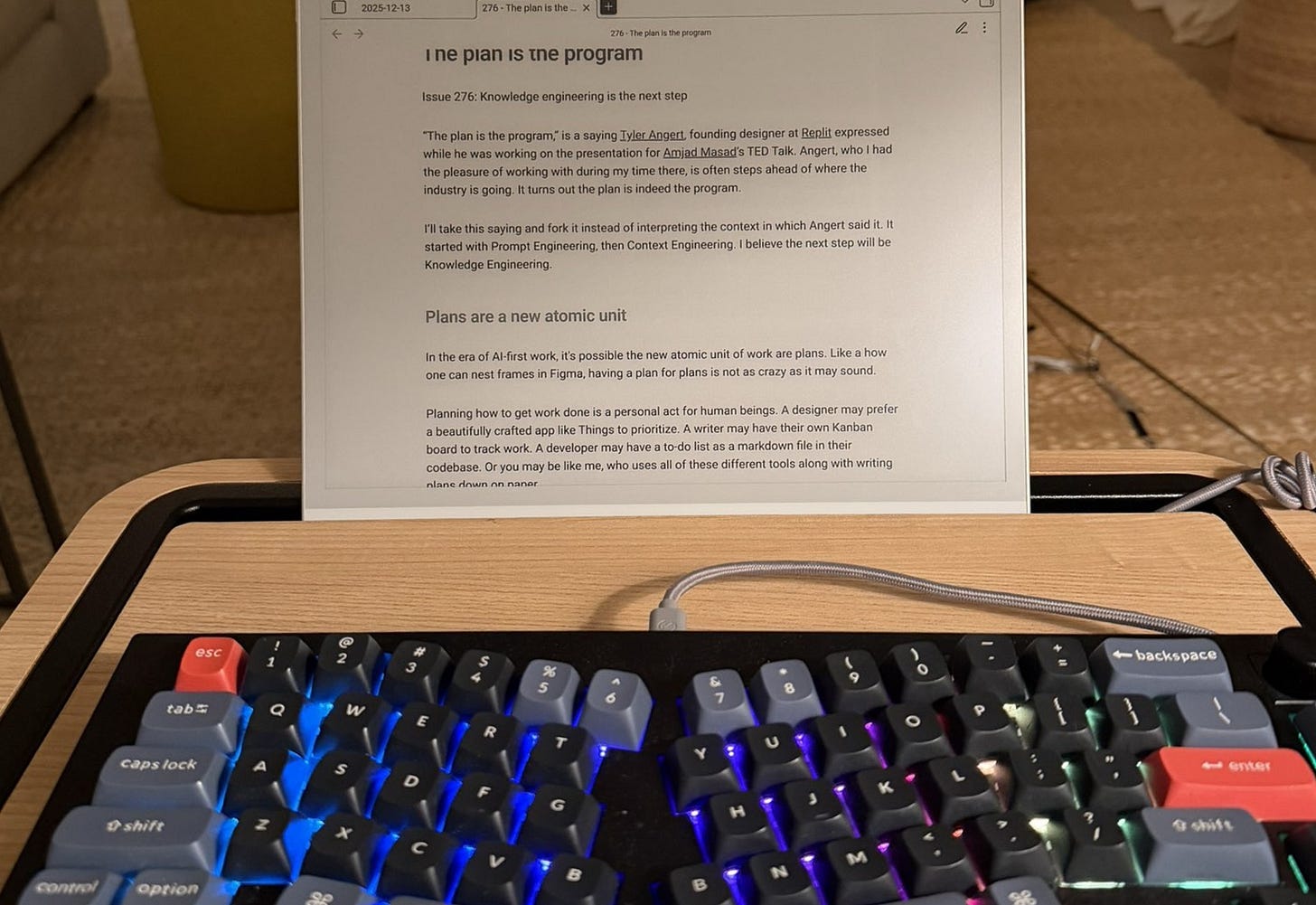

I didn’t go fully analog. That part was deliberate. My e-ink tablet stayed as part of the natural light week. I recently purchased a Boox Note Max because it does not have a front light. I didn’t want a device that would tempt me to sit in bed with a “less worse” artifical light. I can draft, reorder, and read without the constant visual signal of light being emitted at me. It gives me continuity without pulling me back into the same attentional state as a laptop or phone. My e-ink tablet serves as a research, writing, and sketching tool.

Fewer tools, fewer affordances, fewer paths forward. The work slows down just enough for thinking to catch up. Handwriting is slower. You can’t capture everything. You have to choose. That friction forces prioritization early, rather than deferring it to editing later. Structure emerges before volume.

Typed text feels provisional and disposable. Handwritten notes feel committed, even when rough. That changes how long I’m willing to stay with an incomplete thought before moving on.

Maintenance, not withdrawal

I didn’t arrive at this practice because I distrust software. I arrived here because I use it heavily.

Modern tools are excellent at execution. They are less good at recovery. Systems optimized for speed and responsiveness don’t include natural pauses unless you add them deliberately. This is me adding one. If I return clearer—more structured, less reliant on momentum—then it worked. Not because technology was the problem, but because recovery was missing from the system.

Sustainable creative work doesn’t require opting out. It requires cycles. Intensity followed by repair. Light followed by dark.

Natural light week isn’t a retreat. It’s maintenance for my mind and body.