My 2026 focus areas

Issue 279: Where I’m placing my attention this year

The conclusion of 2025 brought with it the annual ritual of prediction posts for the new year. I enjoy reading them. Most are written in good faith and are thoughtful. However, I find myself increasingly uncomfortable with the posture as we navigate high displacement variance. We are in a period where foundational assumptions are shifting at the same time. Interfaces are unsettled, abstractions are collapsing, and roles are blurring faster than titles can keep up. In moments like this, prediction feels less like foresight and more like premature compression.

I’m reframing predictions slightly. I’ll frame it on where I’m putting my attention based on trends. What follows isn’t a forecast. It’s a map of interest areas where I plan to spend time going deep. It’s both driven by personal curiosity and a reflection of patterns I’m seeing repeatedly across tools, teams, and workflows. All of it is about developing fluency rather than certainty.

These areas are not independent and compound. Together, they point toward a future where the hardest problems are no longer about capability, but about selection and choosing what should exist.

1) The natural language of drawing

We are now seeing other modalities enter the workplace more visibly. Voice is the most obvious example. There has been renewed excitement around conversational and agentic workflows, including teams experimenting with being constantly mic’d up so agents can observe and act. Luke Wroblewski recently shared an example of this at Sutter Hill Ventures.

The modality I find myself returning to again and again is drawing. It is harmonious with writing and natural language. I can write a sentence, then immediately sketch over it. I can draw a shape and annotate it with words. There is no mode switch. Both are simply ways of externalizing thought.

That fluidity is part of why natural language became the first dominant interface for AI. Words are familiar. Typing is low friction. Conversation maps well to how we already reason through ambiguity. It makes sense that chat emerged as the default surface.

What I’m seeing

When I’m working with chat assistants, vibe coding, or image generation tools, I keep reverting to visual annotation. I circle things. I draw arrows. I sketch alternate layouts. Sometimes this happens on my iPad Pro. Other times, it happens on a piece of paper that I photograph and upload.

This is especially true when working on interfaces. Trying to describe spatial relationships, hierarchy, or flow in pure text often requires excessive precision. A single sketch can convey what would otherwise take paragraphs.

I also notice this when reviewing AI-generated outputs. Rather than rewriting prompts, I typically mark up the output visually to show what needs to change. The visual feedback is more precise and less ambiguous than language alone.

What I’m experimenting with

In my own workflows, I’m deliberately starting with visual input more often and using e-ink tablets or pen and paper to create what I think of as visual prompts before touching a keyboard. I want to see how frequently a drawing can replace or augment a textual instruction. This has changed how I think about prompting. Instead of asking the model to imagine what I mean, I can show it. Even when the model cannot directly interpret the drawing yet, the act of drawing clarifies my own intent before translation.

Why this matters

Natural language unlocked generative AI as it lowered the barrier to entry. Drawing may unlock the next phase. In art direction, a few simple marks can carry far more intent than paragraphs of explanation. A strikethrough is not feedback; it is a decision. A loose redraw nearby does not specify an answer; it constrains the space of acceptable ones. Arrows and gesture lines do not describe movement; they instruct it. These annotations work because they encode judgment, hierarchy, and intent without over-specifying outcomes.

As systems become more capable, the bottleneck shifts from generation to alignment. The challenge is no longer getting something produced, but getting the right thing produced. Drawing is one of the most natural alignment tools humans have, especially for visual and structural problems. For an LLM, these marks are not decoration. They are signals about what should change, what should disappear, and what must remain flexible.

Treating drawing and annotation as a first-class modality rather than a workaround feels inevitable. It allows humans to direct intelligent systems the same way they already direct other humans: through fast, embodied, and high-signal visual language.

2) Dynamic interfaces

Almost two years ago, I wrote about Dynamic Interfaces as a speculative direction. At the time, it felt like an idea slightly ahead of its moment. The underlying capabilities were emerging, but the surrounding ecosystem still treated interfaces as something largely fixed. Screens were designed, shipped, and then maintained. Intelligence lived behind the interface, not within it.

That framing made sense then. Most AI systems were still being experienced through static shells. Even when the underlying model was flexible, the interface rarely was. We were experimenting with intelligence inside products, not with the product surfaces themselves. Today, that separation feels increasingly artificial.

What I’m seeing now are not fully realized Dynamic Interfaces, but fragments of them appearing across tools, workflows, and experiments. Small signals that suggest the interface layer is starting to loosen. Personal websites that regenerate themselves instead of being authored once. Chat systems that return structured UI rather than just text. Internal tools where the shape of the interface changes based on who is asking, what they are trying to do, and what the system already knows.

None of these examples, on their own, represents a finished paradigm. But taken together, they point to a shift in how we think about interfaces. Less as static artifacts and more as negotiated surfaces. Less as something you design once and more as something that emerges through use.

What has changed is not just model capability, but confidence. We are starting to trust systems to participate in shaping the interface itself, not merely filling it with content. That trust is tentative and uneven, but it is growing. And once that boundary begins to move, it is difficult to go back.

Dynamic Interfaces no longer feel like a distant possibility. They feel like an incomplete pattern that is already asserting itself in small, uneven ways.

What I’m seeing

One of the clearest examples is Arnaud Benard’s personal website. Arnaud is an AI researcher at Google and a founder I had the pleasure of backing at Galileo. His site regenerates daily using Gemini. It’s a demonstration of how interfaces can become a living surface.

I also see this emerging through protocols like the Model Context Protocol. One proposal that excites me is the idea of extending MCP servers with interactive interfaces. Today, we often see small UI fragments returned inside chat assistants. The more interesting possibility is when larger components and organisms from a design system can be generated, adapted, and recomposed on demand.

At the same time, many products are still bundling intelligence into rigid CRUD shells. You can sense the tension. The underlying capability is dynamic, but the interface remains fixed and not tailored to the end user.

The problem

Most interfaces we use today were designed for a world where software changed slowly and human behaviors can learn the workflows. In today’s world, tha’s inversed and the CRUD apps are now the bottleneck.

That rigidity becomes a liability in AI-native systems. When capability is fluid, but the interface is static, users are forced to adapt themselves to the tool. Chat interfaces exacerbate this problem. Everything is possible, but nothing is obvious. Discoverability collapses. Cognitive load shifts onto the user.

The opportunity

Dynamic Interfaces suggest a different approach. Instead of shipping one interface for everyone, the interface becomes something that can adapt based on context, intent, and history. Larger design primitives can be assembled when needed rather than always present.

The long-term promise is not novelty. It is personalization without configuration. Interfaces that change because of use, not because the user hunted through settings.

In hindsight, we may view rigid CRUD applications as a necessary transitional form. They solved important problems, but they were never designed for systems that could interpret and respond in real time.

3) From desktop to command center

I often think about Jason Yuan’s article on how the desktop metaphor must die. I agree with the sentiment, but the dated metaphor is very much alive in software interfaces. We have already lived through the shift from desktop to laptop to phone. Each transition changed not just form factor, but the relationship between human and machine. If agentic workflows are the future, the next metaphor is not a desk. It is a command center.

What I’m seeing

As more work is delegated to AI systems, the human role changes. Instead of executing every step, we increasingly oversee multiple streams of execution. This is visible in coding, research, planning, and even creative work.

The best references for this shift do not come from productivity software. They come from games. Real-time strategy players are comfortable managing many units simultaneously. Drone pilots operate complex systems through interfaces that resemble game controllers rather than keyboards.

It is not a coincidence that pilots controlling unmanned systems use interfaces inspired by Xbox controllers. The problem is not precision input. It is situational awareness and judgment.

What I’m experimenting with

In 2026, I aim to prototype workflows that resemble command centers more closely than traditional desktops. This includes experimenting with ambient displays, especially e-ink, as a way to present information without demanding constant interaction.

Tools like Claude Code make this experimentation surprisingly accessible. I can describe hardware behavior, wiring logic, and control flows in natural language and quickly arrive at something tangible. That lowers the barrier to exploring what knowledge work might feel like when the human is orchestrating rather than executing.

Why this matters

For many generalist roles, the future may feel less like playing a grand piano and more like playing a DJ set. Knobs, dials, layers, and judgment rather than keystrokes.

This is not a value judgment. It is a shift in where skill concentrates. The craft moves from execution to orchestration.

4) Personal LLMs and agents

When people discuss personal AI, the conversation often shifts to avatars or digital twins. Though I believe this will become a norm, I am less interested in a synthetic version of myself and more interested in continuity and the personal AI as a new second brain.

What I’m seeing

Most AI assistants today are capable, but they struggle with continuity. Each tool develops a narrow, local understanding of you based on recent interactions. One remembers your writing tone. Another remembers a project name. A third forgets everything once the session ends. As you move between tools, that context does not travel cleanly. Preferences fade. Prior decisions disappear. You end up restating goals, constraints, and background that you assumed were already understood.

I first encountered this problem directly while working in health tech, thinking about Health Information Exchange. The hardest challenges were never about storage or throughput. They were about consent, access, and interpretation: who is allowed to see what information, the conditions, and duration. Those questions mattered more than raw capability, and they apply just as strongly outside of healthcare.

This is why digital identity fascinated me long before AI entered the picture. Early efforts like Gravatar were compelling not because they were advanced, but because they hinted at continuity across surfaces. Later, crypto and blockchain explored similar territory. The most interesting aspect to me was the idea that identity and ownership could exist independently of any single application. As AI systems become embedded in daily work, these unresolved questions return with more urgency, not as abstractions, but as practical friction.

The problem

As AI systems generate representations of us, there are few agreed-upon norms around consent, attribution, and usage. Images, writing, and voice can all be remixed with little friction. The internet already struggled with this. AI simply makes the cracks visible.

The opportunity

A personal LLM, to me, is not a personality simulator. It is a second brain that augments recall, pattern recognition, and continuity over time. But that only works if identity and consent are foundational.

The opportunity is to build systems where personal context persists without being exploited, and where the user has meaningful control over how their digital representation is used.

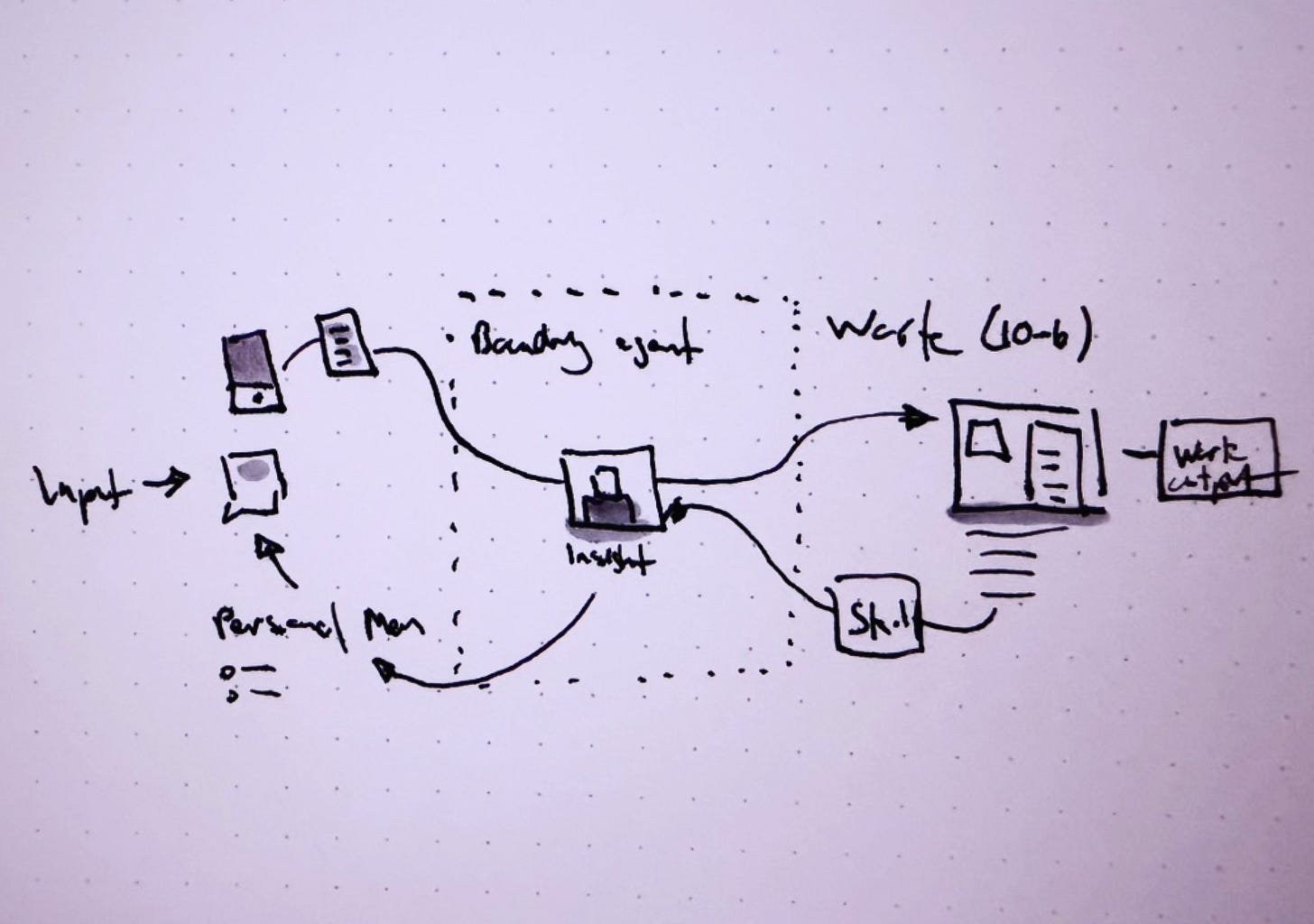

5) Memory interpreters and boundary agents

Memory, in the context of AI systems, is not simply stored information. It is the accumulated context that shapes how a system interprets new inputs, prioritizes signals, and responds over time. Memory determines what an AI “knows” about a user, a task, a domain, and its own prior actions. It influences relevance, continuity, and judgment, not by recalling facts alone, but by weighting experience.

Today, that memory is being accumulated across many separate systems. Each assistant, agent, and tool builds its own partial understanding based on local interactions. One system remembers preferences, another remembers projects, and another remembers tone or habits. These memories rarely travel between tools, and when they do, they lose structure or intent. The result is fragmentation: context is duplicated, re-explained, or lost entirely, even as each system grows more capable in isolation.

What I’m seeing

If you use multiple AI tools today, your memory is scattered. Each system knows something about you, but they don’t collectively know you across your experience stack. Context does not travel cleanly.

At the same time, there is growing interest in shared memory. The appeal is obvious. Less repetition. More continuity. But shared memory without interpretation is dangerous.

Scenarios

Work-to-work memory transfer

Leaving a company today often means starting from zero. Imagine instead a legally portable layer of Personal IP. Not proprietary documents, but patterns of work, skills, and accumulated judgment. Onboarding would translate context rather than erase it.

Personal-to-work memory flow

Much of our best thinking happens outside formal work contexts. Walks, notes, sketches, photos. Today, we duct-tape this together. A boundary agent could decide what crosses into the work context based on intent rather than raw data.

The opportunity

What matters is not unified memory, but interpreted memory. Trusted boundary agents that decide where memory can move, how it should be transformed, and what must remain private.

How these areas connect

What excites me about these five areas is not that they are separate trends. It is that they reinforce each other.

Drawing expands how intent is expressed. Dynamic Interfaces determine how intent is rendered. Command centers reshape the human role. Personal LLMs provide continuity over time. Memory interpreters decide where that continuity flows.

Together, they shift where value concentrates in software. The bottleneck is no longer capability. As AI tools mature, the cost of producing artifacts continues to fall. It is now trivial to generate multiple designs, drafts, plans, or implementations in parallel. What has not scaled at the same rate is the ability to interpret those outputs in context.

Each generated artifact exists within a system. A design sits inside a hierarchy. A piece of code lives inside an architecture. A plan interacts with constraints, people, and incentives. AI systems can generate locally correct solutions without understanding these relationships. Humans are still required to evaluate fit, impact, and risk.

The bottleneck emerges not because systems cannot produce work, but because deciding what work should survive, evolve, or be discarded remains a judgment-heavy task. Interpretation becomes the limiting factor, not throughput.

This is also why MVC continues to decouple. Models become interchangeable. Views become situational. Controllers become agentic. What holds the system together is the interface layer and the memory layer beneath it.

Closing

2025 was the year in which vibe coding was coined and gained momentum. This year, I think people will continue pushing what’s possible and force new professional workflows. We have seen this pattern before. Tools that were once dismissed become foundational once practitioners develop taste, judgment, and responsibility. The question is no longer whether something was generated, but whether it was stewarded.

Vendor lock-in is shifting as well. It is moving away from applications and toward context. If memory and preferences cannot move, choice is an illusion. If they can move safely, competition shifts toward experience rather than captivity.

I am less interested in predicting where this goes than in placing attention where fluency will matter. 2026 does not feel predictable, but it does feel foundational. These are the areas where I plan to do the work. It’s going to be an exciting year.

Hi David, great post! I’m particularly interested in how you use e-ink tablets for context transfer. Could you share a bit more about your specific workflow? Are you sketching on the e-ink screen and then importing those sketches as image inputs into other tools, or do you use a different method to bridge that gap? Thanks!

thank you for what you are doing for the community, interesting insights as always